Go here to sign up for The Embedded Muse.

Go here to sign up for The Embedded Muse.

|

||||

You may redistribute this newsletter for non-commercial purposes. For commercial use contact jack@ganssle.com. To subscribe or unsubscribe go here or drop Jack an email. |

||||

| Contents | ||||

| Editor's Notes | ||||

|

Tip for sending me email: My email filters are super aggressive and I no longer look at the spam mailbox. If you include the phrase "embedded muse" in the subject line your email will wend its weighty way to me. |

||||

| Quotes and Thoughts | ||||

If there is a 50-50 chance that something can go wrong, then 9 times out of 10 it will. Paul Harvey |

||||

| Tools and Tips | ||||

|

Please submit clever ideas or thoughts about tools, techniques and resources you love or hate. Here are the tool reviews submitted in the past. |

||||

| Freebies and Discounts | ||||

February's giveaway is a nice little DMM.

Enter via this link. |

||||

| Musing on Engineering | ||||

Reader Geoff had some interesting thoughts:

|

||||

| Follow-up to Microprocessor History Articles | ||||

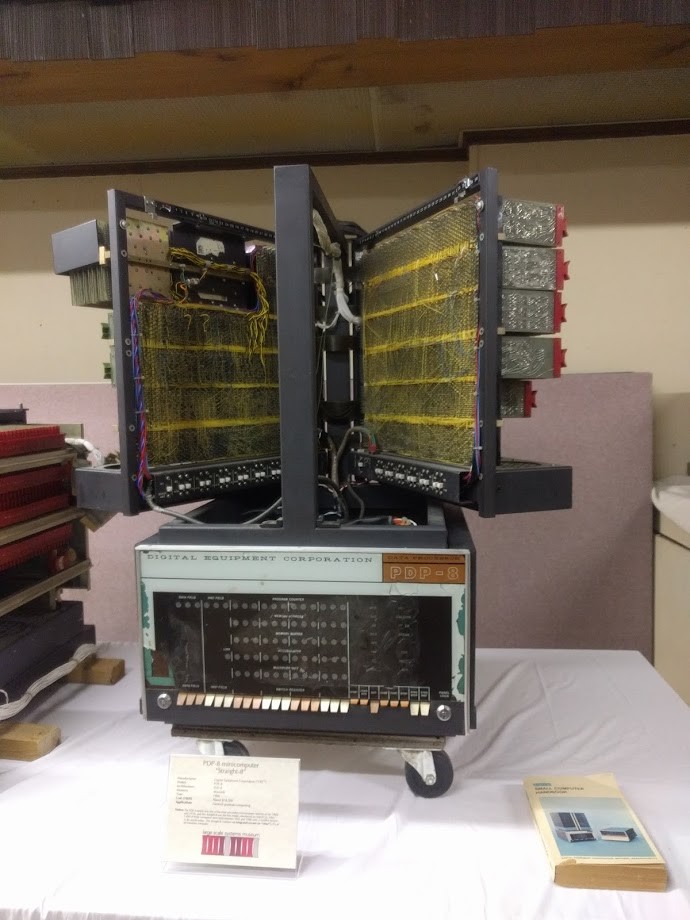

Muses 413 and 414 had articles detailing the history of the microprocessor. In response, Steve Taylor sent this picture of "one of the only known transistor PDP8 in existence".

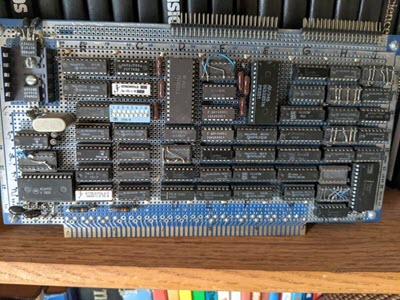

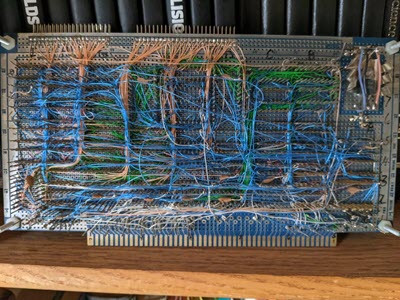

This is at the Large Scale System Museum in New Kensington, PA. Others have recommended it in the past. It's one of the places I'd hope to visit once the pandemic disappears. Maybe in the dim dark vaccinated future I'll try to organize a trip for interested Muse readers. A number of others wrote in. Eric Brewer shared some pictures:

Back in the early days microprocessors required a ton of support circuitry, as this board shows. You may be interested in just how many parts were required to build a working computer. This page shows (about 2/3 of the way down) schematics for a 1974-era 8008 machine. |

||||

| Are We Engineers? | ||||

Are we engineers? In some states that title is restricted to those who pass professional competency tests. The New Oxford American Dictionary (2nd edition, 2005) defines the noun "engineer" thusly: A person who designs, builds or maintains engines, machines, or public works. The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (6th edition) provides a number of definitions; the one most closely suited to our work is: An author or designer of something; a plotter. Neither really addresses what we do, though I have to admit liking "a plotter" as it paints us with an air of mystery and fiendishness. In a provocative piece in the March 2009 issue of the Communications of the ACM ("Is Software Engineering Really Engineering?" by Peter Denning and Richard Riehle) the authors wonder if software development is indeed an engineering discipline. They contend that other branches of engineering use standardized tools and metrics to produce systems with predictable outcomes. They state about software: "[no process] consistently delivers reliable, dependable, and affordable software systems. Approximately one-third of software projects fail to deliver anything, and another third deliver something workable but not satisfactory." That huge failure rate is indeed sobering, but no other discipline produces systems of such enormous complexity. And we start from nothing. A million lines of code represents a staggering number of decisions, paths, and interactions. Mechanical and electrical engineers have big catalogs of standard parts they recycle into their creations. But our customers demand unique products that often cannot be created using any significant number of standard components. At least, that's the story we use. I hear constantly from developers that they cannot use a particular software component (comm stack, RTOS, whatever) because, well, how can they trust it? One wonders if 18th century engineers used the same argument to justify fabricating their own bolts and other components. It wasn't until the idea of interchangeable parts arrived that engineering evolved into a profession where one designer could benefit from another's work. Today, mechanical engineers buy trusted components. A particular type of bolt has been tested to some standard of hardness, strength, durability and other factors. In safety-critical applications those standard components are subjected to more strenuous requirements. A bolt may be accompanied by a stack of paperwork testifying to its provenance and suitability for the job at hand. Engineers use standardized ways to validate parts. The issue of "trust" is mostly removed. Software engineering does have a certain amount of validated code. For instance, Micrium, Green Hills and others offer products certified or at least certifiable to various standards. Like the bolts used in avionics, these certifications don't guarantee perfection, but they do remove an enormous amount of uncertainty. I'm sure it's hugely expensive to validate a bolt. "Man-rated" components in the space program are notoriously costly. And the expense of validating software components is also astronomical. But one wonders if such a process is a necessary next step in transforming software from art to engineering. |

||||

| Failure of the Week | ||||

Luca Matteini installed the new FTTC/FTTH router, received from Vodafone, I was just checking the statistics to discover that the sent packets are a negative/fractional number...

|

||||

| Jobs! | ||||

Let me know if you’re hiring embedded engineers. No recruiters please, and I reserve the right to edit ads to fit the format and intent of this newsletter. Please keep it to 100 words. There is no charge for a job ad. |

||||

| Joke For The Week | ||||

These jokes are archived here. If it weren't for C, we'd all be programming in BASI and OBOL. |

||||

| About The Embedded Muse | ||||

The Embedded Muse is Jack Ganssle's newsletter. Send complaints, comments, and contributions to me at jack@ganssle.com. The Embedded Muse is supported by The Ganssle Group, whose mission is to help embedded folks get better products to market faster. |