By Jack Ganssle

A Visit to Bletchley Park

Published 6/09/2008

A few weeks ago my wife and I visited Bletchley Park, home of Britain's famous World War II code breakers. I thought the pictures might be interesting to computer folk.

Allan Turing and many other others, both famous and not, worked at Bletchley to crack a number of codes used by the Axis powers. The most famous of these was the German Enigma. Their naval Enigma codes were the most valuable of all due to the amount of shipping being lost to the U-boats. The numbers were staggering, and the allies read intercepted messages, when they could, to route convoys around the wolf packs.

A couple of weeks before going to England Marybeth and I stumbled into the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. The museum has U-505 on display, which was captured and provided hints used in the always on-going process of cracking Enigma's latest encryption settings. It's well worth a visit, but do read "Enigma" by Hugh Sebag-Montefiore before going to the museum for a far different take on the military politics of the taking of U-505 than you'll get in Chicago. The museum is almost worshipful in its admiration of Captain Gallery, who bravely effected U-505's capture. But according to the book, Admiral King considered court-martialing Gallery since his failure to sink the U boat could have lead to the German's getting wind of Bletchley's successes.

Mr. Sebag-Montefiore's family actually owned Bletchley Park just before the government acquired it for their code-breaking purposes.

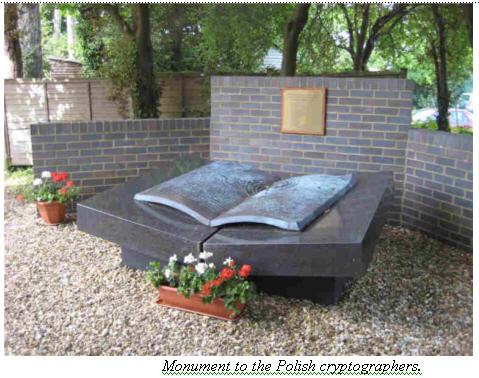

The Enigma machines used three, and later four, "rotors" plus a plugboard to encipher plaintext. To read these messages the allies had to figure out rotor settings. In the 30s a small team of Poles, using information leaked by a German to French intelligence officers, worked out the Enigma machine's design and some of the critical algorithms needed to crack the codes. The Polish team gets scant respect in modern coverage of the Enigma saga, but the Park has a monument dedicated to them.

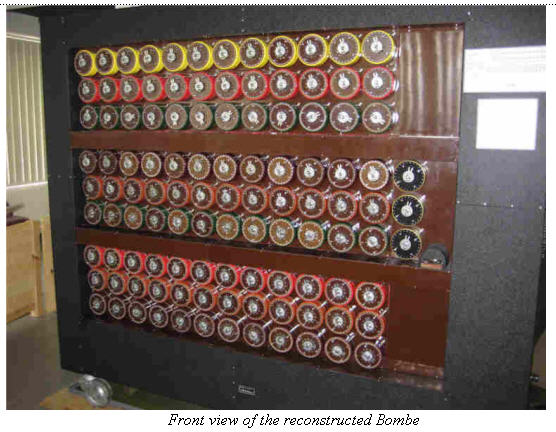

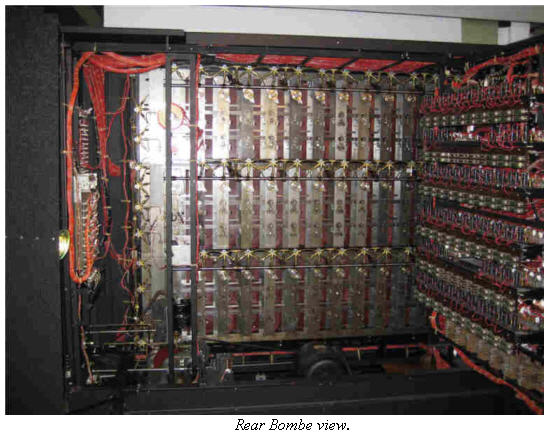

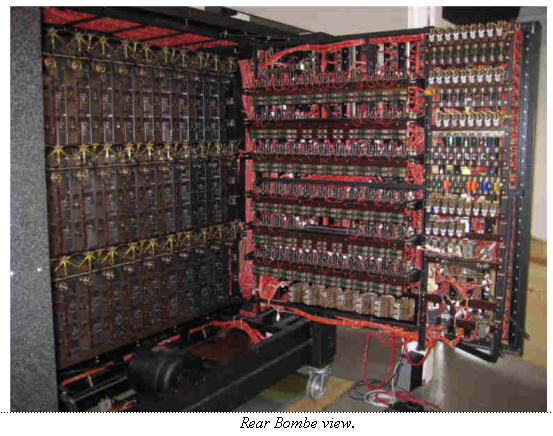

At Bletchley, Turing and others built the so-called "Bombe" machine to help work out Enigma rotor positions. Hundreds were built and deployed around Britain and the US. Few survived the war (though rumors persist several were used through the 50s on Soviet codes before being destroyed). One has been reconstructed and works. Here are a few pictures:

Why the name "Bombe?" There are several theories; the one that appeals most to me is that the Polish geniuses who initially cracked Enigma invented the basic ideas behind the machine while eating an ice cream called "Bomba," which the British Anglicized to "Bombe."

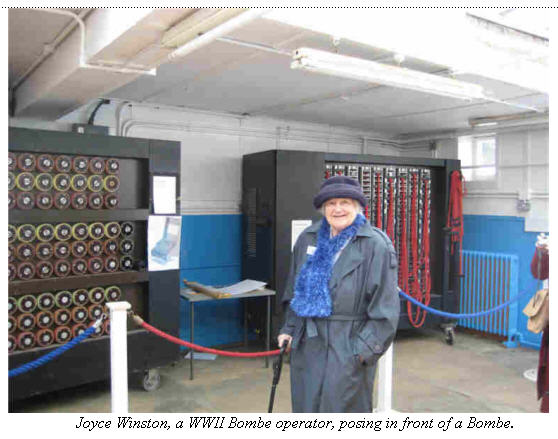

Despite the small group, imagine our surprise - and delight - to find that one member of our tour was Joyce Winston, n‚e Meyer. Joyce had worked in the Park during the war as a Bombe operator! She was one of the 6000 or so WRENS assigned to the project, and now, 60+ years later, escorted by her son and daughter-in-law, visited a scene of her youth. Her memory had some big gaps but after the tour she talked to me excitedly about her work and living quarters nearby.

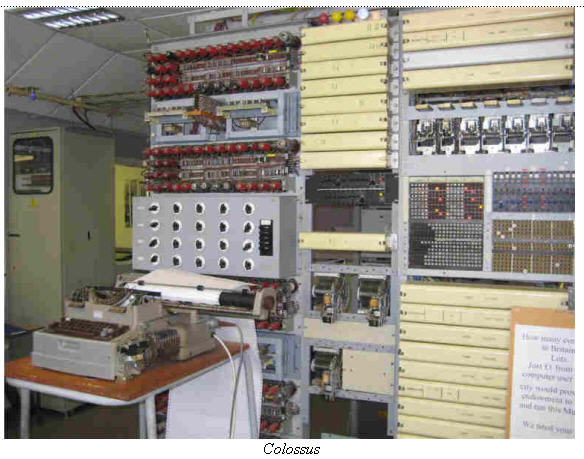

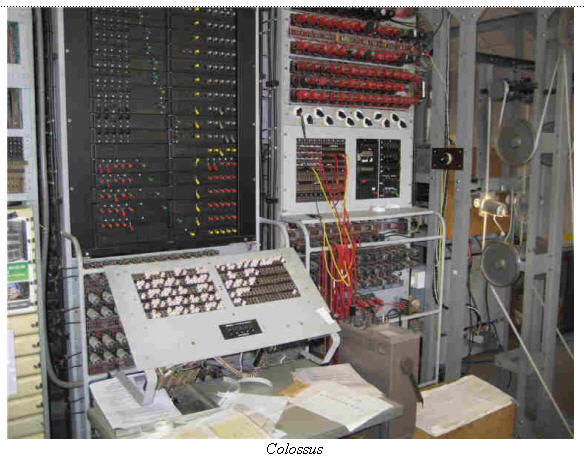

The Bombe is not electronic; it's electromechanical. That's not to demean the machine at all, but my biggest interest in visiting the Park was to make a pilgrimage to Colossus. The British claim it is the first electronic digital computer. I no longer make any claims about historical firsts as there's always some expert who unveils some heretofore barely-recognized first. Maybe the German Konrad Zuse had some earlier technology (for computer buffs a visit to the Deutsches Museum, which shows off some fascinating Zuse machines, is a must-see).

Conventional history posits ENIAC as the first electronic digital computer. Note that "programmable" isn't an included adjective, since the ENIAC originally wasn't particularly programmable, though later modifications changed that. Colossus, though, was a heavily-guarded secret whose existence wasn't revealed till the 70s, and which wasn't acknowledged till 2000 by the British government. So ENIAC priority claims were made while the truth remained classified.

Colossus was not built to break Enigma. It was meant to help decipher the German High Command's Lorenz code, which was much harder to crack than Enigma. Lorenz encryption machines had 12 encrypting rotors compared to Enigma's 3 or 4. Since each rotor gave 26 possible scrambles, the permutations defy imagination.

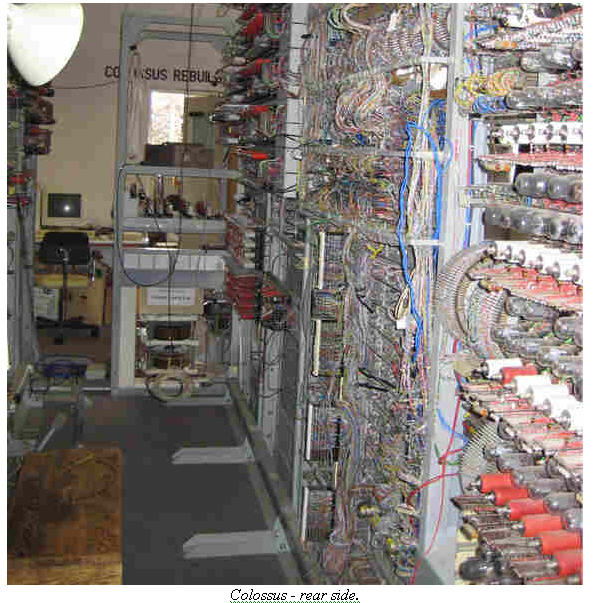

No Colossus survives. Yet Tony Sale managed to build one from scratch based on incomplete and fragmentary information he garnered from a meager partial schematic, plus interviews with some of the Colossus engineers. The reconstructed machine actually works, and was running while we were there. It's simply breathtaking.

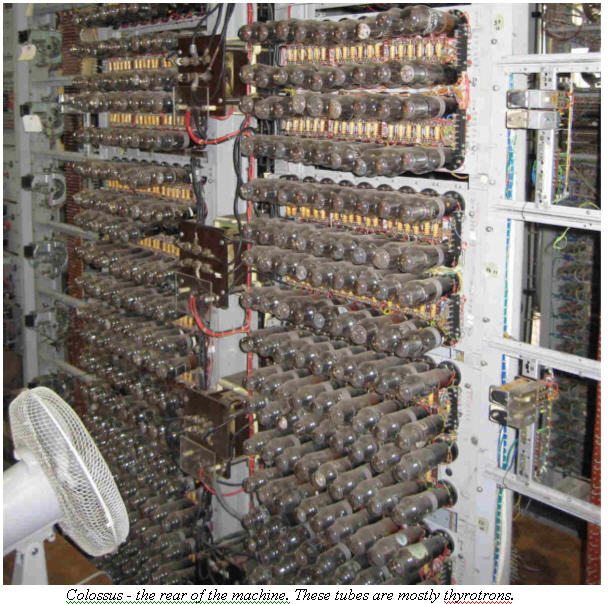

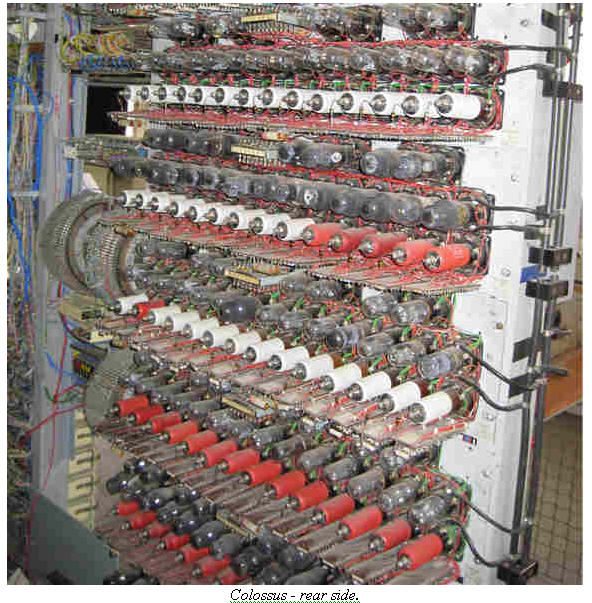

The Colossus prototype was so successful that practically before it ran follow-on versions were ordered. Version 2 had some 2400 "valves," or vacuum tubes. Most were single-pentodes. Now we can't design a telephone with less than a couple of million active elements, so building a machine with 2400 transistor-equivalents was quite the feat. I hung around after the tour wandered off and chatted up the Colossus docent, an ex-Honeywell engineer. He showed me hand-drawn sketches of Colossus circuits for basic logic elements, which used extremely-clever suppressor-grid arrangements to get more work out of a simple circuit. I wish I'd taken pictures of the schematics. Tommy Flowers designed the machine, and he must have been an engineering genius. It's a shame his creation went unrecognized for so long.

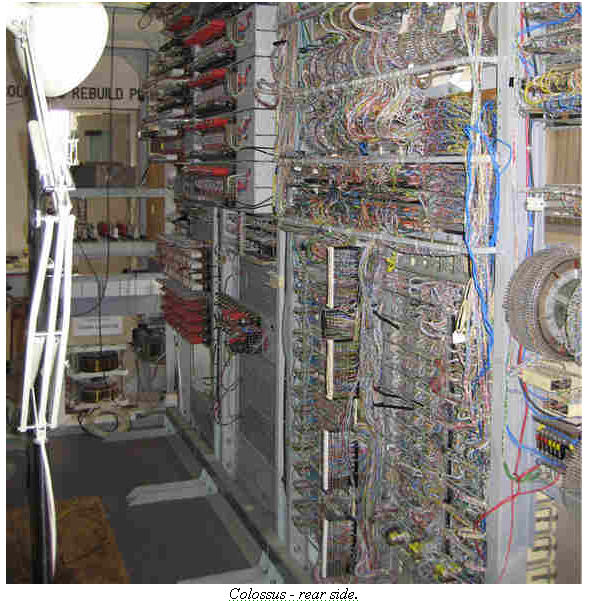

The rear of the machine is off-limits yet houses the most interesting electronics. But the docent was responsive to an engineering discussion and let me behind the ropes. Here are a few pictures:

At least one of the rebuilt Colossus's vacuum tubes (uh, "valves") is 64 years old and still going strong. When Colossus was first proposed skeptics felt it would be so unreliable, due to tube failures, that the machine wouldn't be practical. Flowers realized most tube failures occurred at power-on, so left the machine on 24/7. The cost of electricity prohibits that today, so the replica uses an automated variable transformer to slowly, over the course of minutes, bring the filaments up to rated voltage and thereby avoid thermal shock.

Finally, I was struck by the "Engineer's Lament," posted inconspicuously in a display case: